Hello everyone and welcome to the Chartbook! This issue will discuss several recent themes in USD money markets: Treasury Bills and repos occasionally trading at negative yields, record low Libor rates, rising usage of reverse repos and ‘Other Deposits’ at the Fed, and some theories on how they fit together. While there are many factors behind each of these individual events, this Chartbook will attempt to present a framework that connects the main drivers. To begin, let’s have a look at the big-picture of US bank balance sheets, starting with the Federal Reserve!

Balance Sheets

Most Thursdays around 4:30pm ET, the Fed publishes its H.4.1 release (posted here), which details the assets and liabilities on its balance sheet as of the close of the previous day. The latest release gives us the composition of the balance sheet as of this past Wednesday, April 28. For easy viewing, it is convenient to lay this out as two stacked columns side-by-side, as shown in the chart below.

Starting on the left column, we see that the Fed holds about $5 trillion in US Treasuries and a bit over $2 trillion in Agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which combined make up the bulk of total assets. The remaining assets are made up of loans to Treasury-sponsored credit facilities, credit extended through the discount window, and other miscellaneous items. Currently, the Fed is actively growing its balance sheet by purchasing Treasuries and MBS on the open market, which are added to this asset column. By purchasing assets, the Fed also expands the liabilities side of its balance sheet, creating new Fed liabilities as an asset for the counterparty selling their Treasuries or MBS.

Since Fed liabilities are a monetary asset for the rest of the financial system, this discussion will focus more on the right column, where the categories are broken down in more detail. At the bottom is a bit over $2 trillion of currency in circulation, which are physical Federal Reserve Notes currently outstanding. Immediately above this is just under $4 trillion of bank reserves, which are deposits held by commercial banks at the Federal Reserve. To put more physical currency into circulation, the banks can request that some of their reserves be converted into Federal Reserve Notes, which are then printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (an agency of the US Treasury) and delivered to the bank for distribution. When the Fed purchases securities on the open market, this creates new bank reserves as the primary dealer clearing banks receive them as assets in exchange for primary dealers selling securities to the Fed.

Moving further up the column we have about $1 trillion in the Treasury General Account, which is an account with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that holds most of the Treasury’s cash. Before 2008, the Treasury held most of its cash with commercial banks, so changes in its cash holdings would have minimal or no effect on the Fed’s balance sheet. After the financial crisis, however, the Treasury moved its cash holdings to the Fed, which means they now have a different and substantial effect on money-market structure. When the Treasury sells bonds at auction, the buyer’s bank sends reserves into the Treasury General Account, which shifts the composition of the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet. Conversely, when the Treasury spends money or pays down debt, this shrinks the Treasury General Account and credits a the bank of the receiver of funds with reserves, shifting the balance sheet composition in the other direction.

Above the Treasury General Account is about $300 billion in ‘Other Deposits’. These are other accounts similar to the one held by the US Treasury, but for key non-bank financial institutions. These include government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie/Freddie and the Federal Home Loan Banks, as well as systemically-important financial market utilities (SIFMUs) such as The Depository Trust Company (full list of SIFMUs here). When these institutions send or receive payments with the rest of the financial system, it also causes a change in bank reserves and shift in the Fed’s balance sheet similar to the Treasury General Account.

Above the ‘Other Deposit’ accounts are foreign (purple) and domestic (orange) reverse repo balances. The foreign reverse repo service is provided by the NY Fed to foreign central banks and governments that have accounts with the Fed. At the end of every business day, the cash in eligible accounts is ‘swept’ into reverse repos, meaning it is exchanged for Treasuries from the Fed’s portfolio which are then repurchased by the Fed the next day at a price reflecting policy overnight rates. The foreign reversed repo service has been around for decades and is unlimited in capacity, but only available to sovereign or official accounts. The more recently-introduced domestic reverse repo service, on the other hand, is available to US banks, some government-sponsored enterprises, and large money-market funds, but currently capped at a limit of $80 billion per participant. The mechanics of domestic reverse repos are similar, the Fed allows participants to temporarily exchange cash for Treasuries from the Fed’s portfolio and reverses the transactions the next day, currently paying an implied rate of zero. Combined, the domestic and foreign reverse repo facilities held about $500 billion at the time of this latest release.

Finally, at the top of the column, there is a thin sliver of other liabilities and capital, which are other items such as central bank currency swaps and shareholder equity that make up the balance of the Fed’s liabilities. For this Chartbook, let’s focus on the categories highlighted and look at some trends over the past few years!

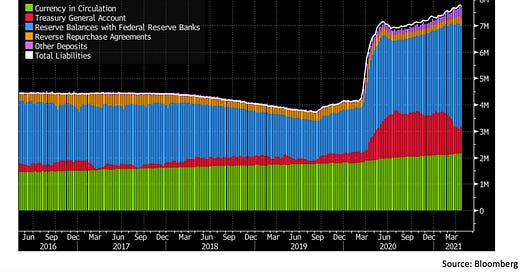

In this chart, we see the evolution of five major items on the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet since 2016. At the bottom we again have currency in circulation (green), which has increased at a relatively steady rate over this period. Directly above this is the Treasury General Account (in red). In the first half of 2020, the Treasury issued a large amount of debt (mainly bills), which caused the Treasury General Account to grow rapidly. In 2021, on the other hand, the Treasury spent more from the Treasury General account than new issuance brought in, causing it to begin shrinking in size again. Also during the first half of 2020, the Fed purchased a large quantity of assets, which resulted in bank reserves (blue) surging during this period. In the second half of 2020 this pace moderated, but reserves have started to grow quickly again as the Treasury General Account started shrinking this year. Finally in orange and purple we see the reverse repo balances (combined foreign and domestic here) and ‘Other Deposits’ account, respectively. These accounts are smaller and more volatile but have also seen some notable increase recently as the Treasury General Account is being drawn down. As a check, the white line shows total liabilities, which roughly equal the sum of the stacked items below, confirming that we are capturing the vast majority of the Fed’s liabilities in this view. Now that we’ve identified the drawdown of the Treasury General Account as the major current trend, let’s look at what is driving it and what the effects of this are!

This chart shows the total amount of US Treasury Bills outstanding (white line) and net monthly issuance (blue bars) over the past decade (in $ millions). We see that in April, May, and June of last year, the Treasury issued about $2.5 trillion of additional bills in net. Since then bill issuance has fallen below what is necessary to replace maturing bills, so the blue bars have gone below zero and the amount outstanding has started to fall. This is one of the factors contributing to the drawdown of the Treasury General Account. As the Treasury pays down maturing bills, it grows bank reserves by crediting the holders bank accounts (and the bank’s reserve accounts) as discussed earlier. In addition to this, the Treasury has been spending on a number of stimulus programs, which directly increases the reserves of banks receiving the deposits of stimulus checks. Next, let’s follow the flows of bill pay-downs and stimulus deposits to see how the effects cascade through money markets, starting with the effect on bank balance sheets.

This diagram shows the combined balance sheet of the US commercial banking system as given by the latest Fed H.8 release (posted here), in the same format as the Fed balance sheet earlier. In the assets column on the right, we see that the banks hold about $8 trillion in reserves and Treasury and Agency securities, which make up the bank’s high-quality liquid assets (HQLA). Above this are various loans and other assets (including real estate loans not split out here and other forms of bank credit). On the liabilities side, most of the balance sheet is made up of deposits, which is cash held by bank customers in their deposit accounts. The parallels with the Fed’s balance sheet here highlight the hierarchical nature of the monetary system. The Fed holds HQLA in the form of Treasuries/MBS and offers its liabilities as HQLA to the banking system, which offers its own liabilities as cash for the broad public (or HQLA for non-bank financials which are further down the monetary hierarchy).

When the Treasury pays down bills held by a bank, this is simply an HQLA conversion, moving assets from one bucket (Treasury bills) to another (bank reserves). However, when the Treasury pays down bills held by a bank customer, this grows both sides of the balance sheet, adding new deposits on the liabilities side as well as new reserves as assets. Finally, when the Treasury sends out stimulus checks to bank customers, this also grows both sides of the bank’s balance sheet, creating a new deposits and new reserves. We know however (see page 17 of JPM’s Q4 2020 earnings presentation here) that the major money center banks make very little (or even lose money) on new marginal deposits. This is because, as discussed in previous Chartbooks, major US banks are approaching various regulatory thresholds that would increase the cost of further growing balance sheets, which combined with the existing low rates results in negative marginal economics on deposits. This creates an environment in which banks turn down additional deposits from large cash holders (retail deposits are treated more favorably by regulators) and encourage them to place cash with money market funds (MMFs) or on other bank balance sheets instead. This shifts the pressure of Treasury cash flows onto MMFs and institutional treasuries. In the next few sections, let’s look at the effects on these players as they seek to resolve the bank’s deposit issues as well as lose some their own Treasury bills to pay-downs.

Treasury Bills & Repos

When an MMF loses bills or receives new deposits, it usually is required to invest by its mandate, as MMF managers are not paid to sit on idle cash. For large MMFs with access to Fed reverse repos, this is not necessarily an issue. As long as the idle cash does not exceed the $80 billion counterparty limit with the Fed, it can always find a risk-free asset to invest in. For smaller MMFs without access, however, this does present a problem. As Treasury bills are paid down and supply from the Treasury is not abundant, smaller MMFs turn to the Bill secondary market and repos to redistribute their cash to other investors with more options.

In this chart we see the secondary market rates for US Treasury Bills out to one year from maturity. Since the Treasury General Account started drawing down this year, yields have been compressed down to below 5 basis points for all Bills. The yields on the 1 month (white) and 3 month (blue) Bills have even briefly gone slightly negative. This is because while crowding will not make MMFs buy Bills at negative yields, institutional treasuries may do so if they are facing fees from banks trying to turn down additional deposits. If the yield on Bills is less negative than the cost of holding more cash at a bank, it becomes a favorable option for corporations and institutions to buy (slightly) negative yielding Bills.

This creates an unusual situation at Treasury Bill auctions, since despite considering the option in the past (see the note in the August 2012 quarterly refunding statement here) the Treasury does not currently allow Bills to be auctioned at negative yields. This creates a situation where bidders at an auction are guaranteed a profit if they can receive some Bills to re-sell on the secondary market at a negative yield. This situation also occurred in June and September/October of 2015, so let’s have a look at what its effects were then.

This chart shows the secondary market yield (white) and some auction statistics for 1 month Treasury bills in 2015 and recently. The green line shows the 5th percentile yield of bids received at auction, which is usually slightly below the secondary market rate and indicates that some bidders are willing to play it safe and risk a slightly higher price to make sure they get their Bills. The orange line shows the median bid yield and the red line shows the highest bid yield filled (which is the yield all the Bills are issued at). The blue bars in the bottom panels show the bid-to-cover ratio, which is the ratio of the total dollars bid to the value of the Bills being sold. As secondary market yields turned negative in 2015, bid-to-cover ratios spiked, since any auction participant could now receive bills and flip them at a profit. This also resulted in the entire distribution of bid yields collapsing down to zero, since bidding above zero would be pointless as it would basically guarantee an unfilled bid. The most recent 1 month Bill auction on April 29 was the first example of a bid distribution like this in some time, with all filled bids at exactly zero yield. Bid-to-cover ratios have remained relatively stable, but if institutional treasuries keep bidding short-term Bills to slightly negative yields, they may spike much higher in the near future as auction participants seek to arbitrage the spread. Similar pressures can be seen in the repo market, where rates have dropped to near zero as participants with limited capacity seek to redistribute their cash to others.

The chart here shows the weighted average rates for general collateral Treasury (white) and MBS (blue) repos traded through the DTCC GCF platform. These trades represent exchanges of cash for generic unspecified US Treasuries or MBS between dealers. Since general collateral trades through DTCC are netted to minimize ‘physical’ settlement and fungible across different securities of the same type, they can be seen as the baseline price of cash in the inter-dealer overnight repo market (some good detail on the GCF repo service here). The pink line shows the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which is a composite repo rate calculated by the Fed as a benchmark. All of these rates have dropped to very close to zero, but so far have not broken below except for very brief occasions. This shows that there are market participants willing to take cash should repos trade significantly negative, suggesting the redistribution to participants with capacity is occurring. Now let’s turn to some other rates that may be affected by participants not so capable of redistributing their funds on demand.

Other Short Term Rates

When an institutional treasury loses Bills to pay-down or is charged fees on new deposits, it has several options besides going to the secondary Bill market to invest its cash. Large cash holders can buy slightly longer term Treasury debt on the international markets, where sellers may have access to the domestic or foreign reverse repo pools. They could also take some more credit risk instead of extending maturity by lending in FX swaps or buying commercial paper or a certificate of deposit from a US branch of a foreign bank, which rely on these kinds of transactions for some portion of their dollar funding. This moves reserves to foreign banks, which have more capacity to warehouse them, but puts pressure on rates in FX swap and offshore USD markets, so let’s have a look at what has been going on there.

This chart shows the Euro (white) and Yen (blue) 3 month basis spreads against the US dollar. The basis spread is a measure of how much currency swap rates deviate from theoretically arbitrage-free interest rate parity pricing in the real market (where swaps are priced at exactly the rate differential between the two currencies). Euro and Yen basis spreads are structurally negative due to the fact that financial institutions with liabilities in those currencies hedge their US dollar assets by borrowing USD in the swaps market. As an interesting side note, Australian dollar basis spreads are structurally positive for the opposite reason: Australian banks fund themselves by borrowing in US dollars heavily, so they hedge this liability by lending US dollars into USD/AUD swaps. These differences are discussed in more detail here for readers interested.

What is key to note here is that Euro and Yen basis spreads have gotten close to zero so far this year, but have not gone positive. This suggests that while US dollars are being readily supplied to foreign banks in the swaps market, there is not enough crowding to shift the structural balance of US dollar currency basis. This is also reflected in the spreads between offshore dollar rates and US money markets.

In the chart above the white line shows the spread between a 3 month Forward Rate Agreement (FRA) and the 3 month overnight indexed swap (OIS) which pays a rate based on compounded Fed Funds rates over the period. A FRA functions similar to a futures contract on its benchmark rate (in this case Libor) and rolls every 3 month in mid-March, mid-June, mid-September, and mid-December. These contract rolls result in discontinuities in the FRA-OIS spread price series so the ‘spot’ Libor-OIS spread is also included in blue to avoid confusion. As we can see, offshore dollar rates have also compressed to multi-year lows, indicating an ample supply of reserves in the market, but so far the pressure has not resulted in an inversion of the existing market structure.

To summarize, let’s take a step back and observe these themes from the point of view of two fundamental variables in money markets: price and quantity. The drawdown of the Treasury general account is a driver of quantity, the composition of liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet simply must change due to the underlying mechanics. However, bank’s capacity to absorb large quantities of reserves is constrained by the regulatory costs of increased size and poor economics of additional deposits. Since capacity is limited, prices will adjust to where they make up for the cost of additional capacity (deeply negative rates) unless uncapped capacity at a fixed price is available elsewhere. The Fed recognizes that it cannot control prices and quantities simultaneously, which explains why it has made notable effort to promote the use of domestic reverse repos as an effectively uncapped facility (see expansion to include smaller money market funds here). This, combined with the uncapped foreign repo pool to capture Bill pay-downs and reserves finding their way to foreign central banks and the ‘Other Deposit’ accounts for key institutions normally active in the repo market has created a very large supply of capacity at zero yield. As the transformation of Fed balance sheet liabilities continues to take place, these facilities are absorbing the excess quantity, and preventing excess volatility in the price of money market rates.

This last chart shows the quantities being absorbed by each of these Fed facilities, which in total is now approaching $1 trillion. All three surged in the first quarter of 2020, as central clearing counterparties raised margin requirements (boosting Other Deposits) and institutional cash pulled back from lending to counterparties with credit risks and buying then-negative-yielding Treasury bills (boosting all three). Most of this surge was reversed in the second half of 2020 but quantities have started rising again this year. This rise will likely continue as the Fed balance sheet adjusts and market participants redistribute their holdings to available capacity. For now, despite some pressure, the process seems to be occurring relatively smoothly and money market rates are staying within reasonable ranges.

That will be all for this week! As always, thanks for reading if you made it all the way through and hope to see you back soon for another Chartbook :)

Cheers,

DC

I learned more reading this than days in textbook. Very topical and informative. Congratulations and thank you.

I wholeheartedly agree. I'm waiting eagerly for the next post. Thank you.