Chartbook #17

November 20, 2022

Hello everyone and welcome back! This Chartbook gives a general overview of the market structure around US overnight rates, the different segments in the cash and futures markets, and how they fit together. Since there is way too much to cover in one post, it will includes links to various sources where people can see more of the details and explore the data on their own. To start, let’s look at the risk-free market, which underlies many of the derivative markets that reference overnight rates.

Cash, Securities, and Repos

In the context of USD money markets, the risk-free assets are liabilities of the US Government, which broadly fall under the categories of cash and securities. Cash is any government liability that is instantly liquid at par, while securities are government liabilities that convert into cash at maturity. For simplicity, we can refer to all of the Federal Reserve’s liabilities as cash, including physical cash as well as the Treasury’s General Account (TGA) and other electronic account balances with the Fed. The other side of the market is securities, which make up the liabilities of the US Treasury and the assets of the Federal Reserve’s System Open Market Account (SOMA). At regular public auctions, the Treasury exchanges newly issued securities for cash equivalents, which replenishes the TGA and creates a new benchmark on-the-run security for the tenor issued. In addition to buying or selling securities for cash outright, participants in USD money markets have the option to repo, where a trade in the opposite direction at an agreed price is set for the near future. Since repo effectively shortens the duration of securities to the term of the repo, we can look at repo cash lending as “securities repoed in” and repo cash borrowing as “securities repoed out” within the broader balance of cash and securities in the market. The overnight repo rate, as the market yield on cash (or zero-duration securities), plays a key role in this balance, so let’s turn to it next.

The diagram shows the various participants in the US government securities and repo markets, along with the Treasury and Fed accounts already described. At the center of the private sector of the market are the securities dealers, who are involved in most trades in some capacity. On the liabilities side of their balance sheet, dealers borrow cash in tri-party repo to fund their operations. The tri-party descriptor here means that the counterparties use the services of BNY Mellon (the only active tri-party agent) to custody the cash and securities involved. Since this makes it easier for non-specialist firms to participate, money market funds, cash-rich corporates, and many fund managers lend cash in tri-party repo to generate yield. When demand from dealers is not enough to absorb the supply of cash available, the Fed can also drain cash from the tri-party repo market into the reverse repo facility (RRP), which it has done a lot lately. The dealers may also redistribute cash and securities to each other in the interdealer market, and trade securities outright or in repos with customers. The largest and most well-established dealers are given the status of primary dealer by the Fed, which allows them to participate in monetary policy operations and borrow securities from the SOMA if needed. To maintain the privilege of transacting directly with the NY Fed, the primary dealers must agree to absorb their share of any securities not purchased by other bidders at Treasury auctions, and generally keep a reliable track record and strong balance sheet metrics.

It is important to note that a large part of this market is not directly observable. We can see some statistics on the primary dealers and the tri-party market, and reconstruct to some extent other parts of the market, but large portions are fairly unknown even to regulators. Away from the standardized infrastructure of clearinghouses and tri-party agents, uncleared bilateral repo is a little-reported market where trades are negotiated and settled privately between the two counterparties. In a recent report on work to improve Treasury market stability, comments on uncleared bilateral repo noted that:

Much of the activity in this market takes place over the phone or through electronic chat messages, leaving it to the participants to determine what information they record on a trade.

So when looking at repo rates, let’s recognize that we are always looking at just a subset of the market, and that conditions may be different in other areas. To list out the different segments, we can look at several variables:

Tri-party or Bilateral: does the trade use BNY Mellon as a tri-party agent?

Interdealer or Dealer-to-Customer

Cleared or Uncleared: is the trade processed by a clearinghouse like the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation?

General Collateral or Specific: is the securities leg of the trade in a specific security or any generic security?

With these categories and their cross-tabs in mind, we can now look at volumes and rates in the repo market in more detail.

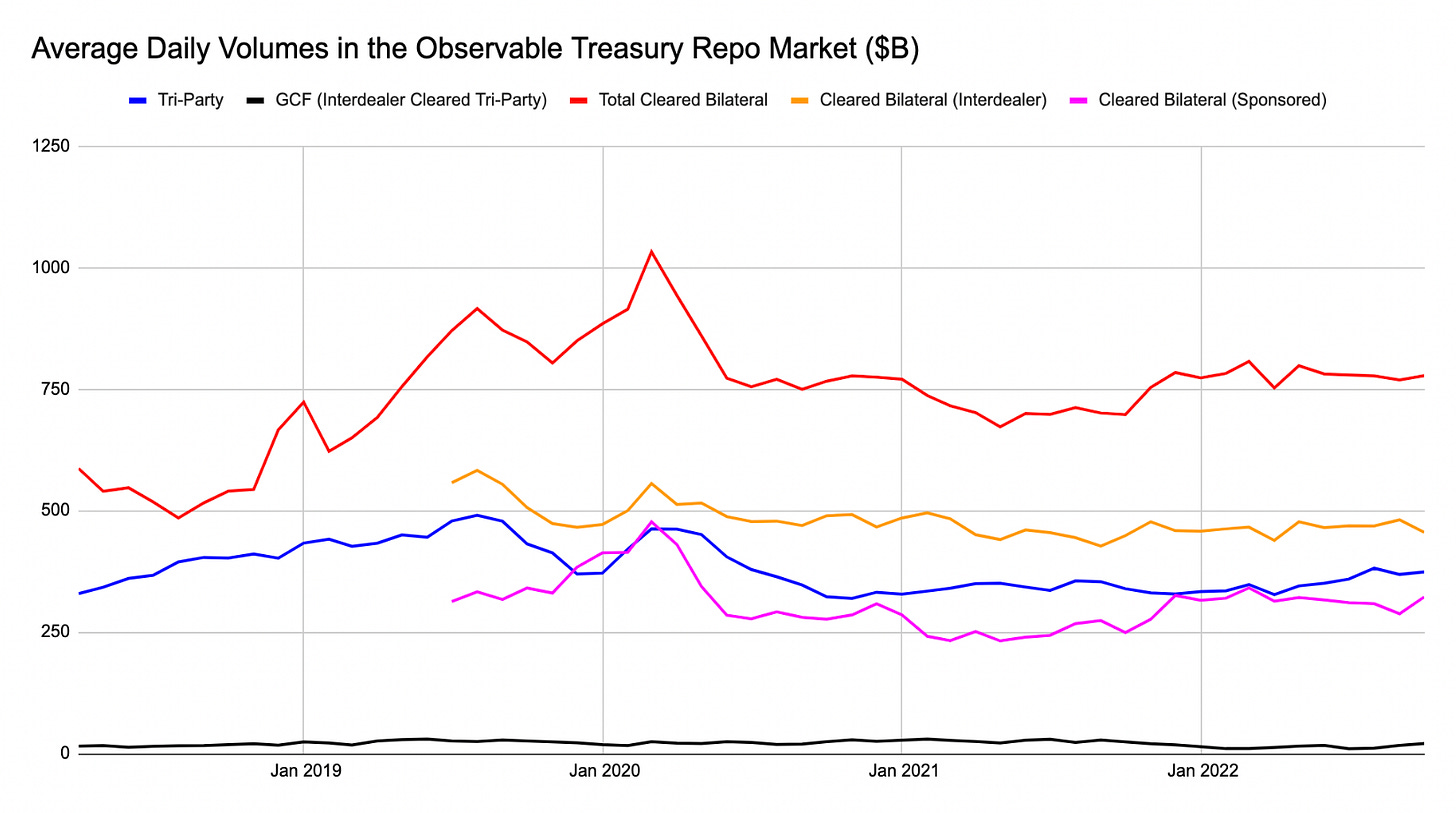

This chart shows average daily volumes for segments of the market that are either intermediated by BNY Mellon as a tri-party agent or centrally cleared by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC). Starting with the blue line, we see that tri-party volumes are generally between $350B and $500B a day. Note that since cash lenders usually do not care what securities they repo in, trades in this segment of the market are for general collateral. A small additional segment of tri-party repo is shown by the black line, which is the GCF Repo service. As a service provided by FICC, GCF repo is centrally cleared and gives participants the benefit of netting positions at the clearinghouse for capital efficiency. However, since the GCF service is also for general collateral, it cannot be used by dealers to obtain a specific security, only to borrow or lend cash. Typically, dealers source most of their cash from outside the dealer system and charge a premium to redistribute it to other dealers, so volumes in GCF repo are about 10% of the rest of the tri-party market and rates are usually higher.

Then there is the bilateral market, for which we can only really see the portion that is cleared by FICC (shown by the red line). These repos trade against specific securities, so every individual bill, note, or bond issued by the Treasury has its own rate in the bilateral cleared repo market. The distribution of repo rates in this market is thus wider than the distributions in general collateral markets, since it depends on the supply and demand for particular securities as well as cash. In the more recent data, we can separate interdealer transactions from transactions between dealers and large customers, who can now gain access to FICC through Sponsored clearing. This split is shown by the yellow and pink lines starting around mid-2019.

Though we cannot know exactly which securities are in highest demand from the public data, we can get a rough idea from the rates paid by dealers to obtain securities temporarily from the Fed in SOMA lending. Generally, the most traded Treasury securities are the most recently issued on-the-runs and the most favored by the delivery requirements of futures contracts (the cheapest-to-deliver). When there is volatility in Treasury rates and large market imbalances, there tends to be high volume and cross-market activity in these active securities, which sometimes spills over into the repo market.

This chart shows the rate at which primary dealers borrowed on-the-run 2 year notes from the Fed’s SOMA portfolio this year. Through the securities lending operations, dealers can temporarily exchange any Treasury security for a specific issue the Fed holds in inventory, at a market determined rate. The spikes on the chart indicate days when dealers paid a high premium to borrow these notes from the Fed (which coincide with volatility in 2 year yields). This tells us that the notes were likely also trading “special” in the repo market those days, meaning they were in high demand and cash repo rates against them were well below most similar securities. Since large customers often trade arbitrage strategies involving the most active securities, there is probably a material overlap of Sponsored volume with these on-the-run, cheapest-to-deliver, and special securities (though it is hard to know how much exactly).

Specific security rates, however, do not represent the true cost of financing more broadly, so they pose an issue for derivative contracts referencing repo rates. Traders using derivatives typically want exposure to some trimmed median of short-term cash rates, excluding volatile outliers. The most widely referenced repo rate, SOFR, solves this by excluding the bottom quartile of trading volume in the bilateral cleared market. So let’s move on to SOFR, and see how the reported data can shed some light on what is going on in these markets.

What is SOFR, Really?

According to the NY Fed, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) is “a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by Treasury securities”. In more practical terms, the daily SOFR print is the volume-weighted median of some portion of the observable repo universe described earlier, rounded to the nearest basis point. Along with the SOFR rate, the NY Fed publishes two additional reference rates, daily volumes, and some rate percentiles as part of the data release. The three subsets of the repo universe referenced are:

Tri-Party General Collateral Rate (TGCR): Overnight tri-party trades for general collateral reported by BNY Mellon, excluding any interdealer GCF trades

Broad General Collateral Rate (BGCR): Same as TGCR plus overnight interdealer GCF trades reported by FICC

Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR): Same as BGCR plus also bilateral cleared trades reported by FICC, excluding the bottom quartile of bilateral trades as “specials”

Given how the rates are constructed, we can start with TGCR, which generally reflects the rate at which dealers are borrowing from cash lenders. Since this rate competes with many other cash equivalents, such as the Fed’s RRP facility, we would expect the distribution of TGCR to be fairly narrow and close to the rate on alternatives. Moving on to BGCR, adding interdealer repos does not really change much, since they are usually less than 10% of BGCR volume. When interdealer repo trades at a high premium, however, we can see some effects, especially in the “tails” of the BGCR distribution.

Finally, SOFR includes specific collateral trades with a broader rate distribution, and introduces some directional bias by trimming the bottom quartile. This means we should expect SOFR to generally print higher than its two subcomponents, unless well over half of total bilateral cleared volume is trading below BGCR.

This chart shows the median rates in each of the three reference samples, relative to the Fed’s RRP facility rate. As expected, adding interdealer trades to tri-party does not change the median very much, so BGCR and TGCR are effectively the same line. Also as expected, SOFR is a few basis points higher than the tri-party rates typically. The overall level of repo rates relative to RRP depends on the balance of cash and collateral in the market. When cash is scarce and dealers need additional funding, repo is volatile and trades above the RRP rate, as it did prior to the repo market events of September 2019. After 2020, cash became much more plentiful in the repo market and started to build up in the Fed’s RRP facility, driving repo rates lower on a relative basis. As rate hikes began this year, repo rates lagged further, now trading a few basis points below the RRP rate on a typical day. This indicates that the median dealer is not really competing for funding, as there is plenty of cash available to meet their operational needs, even at a slight discount.

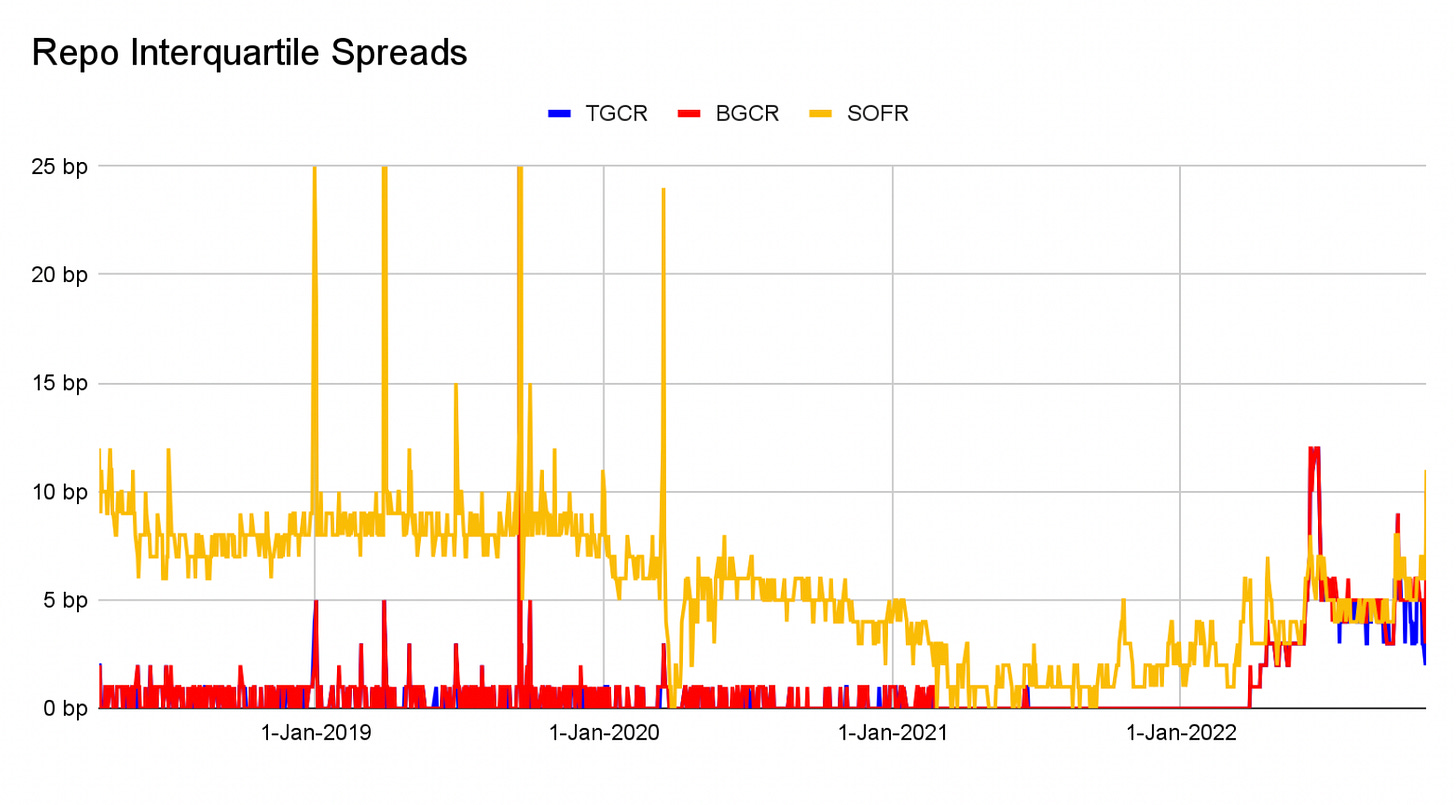

Now let’s turn to the interquartile spreads, which show the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile for each reference rate. For the tri-party rates, this is typically 1 basis point or less, since most of the distribution trades very close to the median. As the Fed started hiking rates recently though, the interquartile spread in BGCR and TGCR has widened to about 5 basis points. This is probably due to some combination of the rapid pace of hikes, relatively low repo demand from dealers, and incomplete access to RRP among cash lenders. Because it includes the specific collateral trades, SOFR has a wider interquartile range. Prior to 2020, this was around 10 basis points, but as rates everywhere compressed to the zero lower bound in 2021 it got down to just barely wider than the others. Now that rates have risen again in 2022, the SOFR distribution has returned to about 2019 levels of dispersion near the median.

For completeness, we can also look at the tails of the distributions, which are shown here as the 1st and 99th percentiles, relative to the RRP facility rate. One thing to note is that the SOFR tails are not very much wider than the others despite the different sample compositions. This means that bilateral repo, despite more dispersion around the median, does not really have much longer tails on a typical day. Also notable is the fact that the upper tail of BGCR tends to skew higher than TGCR, while the lower tail does not. This is due to the small volume of interdealer trades added in BGCR skewing to the upside as mentioned earlier, so they affect the 99th percentile mainly. Finally, we can note the overall directional skew of the tails. Before 2020, the whole distribution of rates would sometimes spike upward, as dealers paid a high premium on some days to access scarce funding. During most of 2020 and 2021, the tails stayed contained, as rates compressed near the zero bound. Recently though, it has been only the downside tails that have spiked, now in the opposite direction. This tells us there are some lenders who may not have access to RRP who are offering cash at a steep discount to dealers who do not really need it. On the upside, repo rates have been very quiet for almost the past 2 years. The flatline in the 99th percentiles means it is probably just a few small positions being rolled every day at a constant spread to RRP. With near-record AUM in money market funds (about 40% in Fed RRPs), there is no shortage of cash on the sidelines in the repo market, and so far dealers have been able to direct it where needed to absorb any pressure to the upside.

Thus far we have looked at markets in cash and Treasury securities, but there are also many other financial instruments derived from these markets. Now that Eurodollar contracts seem fairly certain to cease trading in April 2023, the SOFR 3-month contract has taken over as the most popular listed short term interest rate derivative. In the last section, let’s turn to the derivatives of SOFR and where they fit into the broader market.

New Rates, New Spreads

Since it is unusual for participants to want exposure to money markets for only one day, derivatives of overnight rates generally do not price based on a single daily print. The most common tenors in futures referencing these rates are 3 months and 1 month, with the rate averaged or compounded over time for smoothing. Once Eurodollar futures cease trading, the three most important listed short-term rate products in the US market will be 3 month SOFR futures (SFR), 1 month SOFR futures (SER), and the long-established 30 day Fed Funds futures (FF). These are of course all closely related, but slightly different, so let’s see the details.

This chart shows the two overnight rates (SOFR and EFFR) and the underlying indexes of the three futures contracts. The most liquid SFR contracts are listed with quarterly expiry dates and reference the compounded SOFR rate between the previous contract expiry and the last day of trading. Every March, June, September, and December, a contract terminates and the final settlement price is determined based on the pink line on the last day. By giving users exposure to the compounded rate over the quarter, 3 month SOFR futures provide a simple and reliable hedge for the general level of money market rates. With a highly liquid outright and options market, the SFR contract is the benchmark for expectations of future short-term rates, and is linked to a wide range of forward looking rates markets. For a more granular hedging product that reflects more of the day-to-day variation in rates, users can look to the 1 month contracts. These expire at the end of each month and reference the arithmetic average of the rates during the month, filling weekends and holidays with the most recent available value. The 1 month SER and FF futures are settled at expiry based on the red and green lines, respectively. To understand why there are two separate contracts, and what the difference is, we need to look more closely at the Federal Funds market and what drives rates there.

Fed Funds is unsecured interbank market on reserve balances held overnight, which effectively function as interbank deposits. Since banks started earning interest on reserve balances (IOR) in 2008 and are discouraged from using much unsecured funding, volume in the underlying market is much smaller than for SOFR, generally by about an order of magnitude. There are two primary reasons for banks to borrow in the Fed Funds market recently — arbitrage and immediate funding needs. Arbitrage opportunities exist because the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), which are government-sponsored, do not earn interest on reserves and keep most of their liquidity in the interbank market. Other banks take this cash from the FHLBs at a few basis points below IOR, earning a small spread for effectively providing deposit services. Some banks do still borrow in the Federal Funds market for real funding needs, but it is generally seen as an undesirable way to source ongoing liquidity. This second type of borrowing usually occurs above IOR, since the borrowers pay a premium to cover an immediate funding need. When cash at banks is plentiful, arbitrage borrowing tends to dominate and most trades in the market occur a few basis points below IOR. As cash gets scarce, real funding demand starts to outweigh arbitrage and the distribution of rates shifts upward. Because the Fed controls IOR and sets a target range for the Fed Funds rate specifically, Fed Funds derivatives provide a very clean exposure to Fed policy decisions, with less noise from the Treasury and repo markets than SOFR.

This chart shows the percentiles of the Fed Funds distribution over recent history, relative to the RRP rate. Since banks can lend in the much larger secured repo market if rates in unsecured Fed Funds get too low, there is very little activity below the RRP rate besides a few one-off trades. The blue and green lines here mark the boundaries of the interquartile range, and the black line is the median that is the official benchmark. Most of the time, this central range of the distribution lands a few basis points below IOR (pink line) as we would expect with arbitrage volume dominating. A notable exception to this is 2019, where Fed Funds traded mostly above IOR due to a tighter market for bank funding and increased real borrower demand. Also on some days in 2016 in 2017, the median would spike down to about 20 basis points below IOR, which was due to arbitrage borrowers increasing the spread at month and quarter ends for balance sheet optics. Finally, we can look at the upside tail of the Fed Funds distribution, shown as the orange line. There is usually at least some real demand borrowing so the 99th percentile represents what a few banks are paying to cover small shortfalls in day-to-day funding. One exception is in 2021, where the whole distribution slipped below IOR for a while and there was only arbitrage going on. In the past few months there has been more borrowing above IOR, though not enough to start moving the central range of the distribution upward. Still, this means at least a few banks are facing small funding gaps at times, so financial conditions have tightened somewhat since 2021. Coming back to the difference between 1 month SOFR and 1 month Fed Funds futures, there is a spread that depends on all of these factors.

If one were to trade a spread of SER vs FF futures for the same month in equal size, their pricing would converge at expiry to the realized spread which is shown in this chart. The difference between the reference rates is influenced by details of the Fed’s monetary policy implementation and conditions in the secured and unsecured funding markets. On one side, we can think of the Fed Funds rate as IOR plus a spread, which is a few basis points determined mainly by bank funding conditions. On the other hand, SOFR is the RRP rate plus a tri-party spread and an additional spread from the tri-party rate. The tri-party spread depends on the balance of cash vs generic collateral in the repo market, and the additional spread is a few basis points related to the segment of bilateral trades in the SOFR universe. So when we see Fed Funds minus SOFR, this is a combination of the IOR / RRP spread set by the Fed and three more spreads in the repo and interbank markets:

EFFR = IOR + [Fed Funds / IOR spread]

SOFR = RRP + [Tri-Party / RRP spread] + [SOFR / Tri-Party spread]

EFFR minus SOFR = [IOR / RRP spread] + three more spreads from above

To summarize the futures market in US overnight rates, there is a general purpose 3-month SOFR contract, a cleaner proxy for Fed policy in the 1-month Fed Funds contract, and a 1-month SOFR contract that can be used to capture various spreads between markets. Hedgers and speculators can conveniently trade SER-FF, SFR-FF, or SFR-SER spreads to distribute these risks efficiently, supporting a liquid market in all three products.

Originally, this Chartbook meant to go further into the relationship with Eurodollar markets, the upcoming conversion of ED futures, and so on… but that is a big topic and probably deserves its own post. So that’s all for now! Thanks for reading if you made it all the way to the end and hope to see yall back for the next one :)

Cheers,

DC

Sources & Links

Data Referenced: Daily TGA Balance, SOMA Holdings, Treasury Auctions, Primary Dealer Statistics, Tri-Party Repo Statistics, SOMA Lending, FRBNY Reference Rates, Sponsored Repo, Money Market Funds

Helpful Primers: Tri-Party Repo, Bilateral Cleared Repo, Ongoing Regulatory Work, Repo Trade Practices, SOFR Futures Spreads

Other Cool Stuff: Mapping Repo Clearing & Settlement, FRBNY Blog Series on Liquidity Part I, Part II, Part III